I BELONG

Written by Marc Canton

June 24, 2008

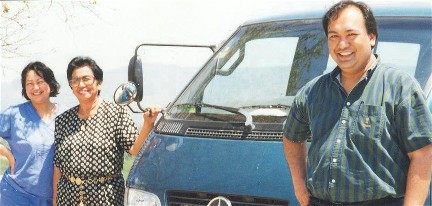

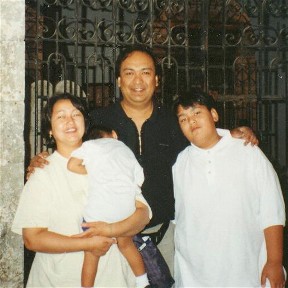

How many times have you heard people say “I belong to this…..or that..”? How many times have you said it yourself? I am very certain that I have said that phrase myself several times. But, have you ever stopped to think what that really means? For me a revelation of sorts happened the first time I took my non-Filipino wife and Canadian-born children on a trip to my native province, Cebu ten years ago, 1998.

I remember I was extremely excited to show my family where I came from, that during our overnight stay in Hong Kong, I could not sleep a wink. I spent most of the night trying to organize my thoughts, prioritizing in my mind what to show my family and where to take them. I wanted them to know that there was more to me than living my Canadian life, working on my Canadian career, and being a Canadian.

Since I left Cebu with my younger brother in 1974, when I was 16 and my brother was 13 years of age, I was hardly exposed to anything Filipino. My family had settled on the West Coast city of Vancouver. There was not a Filipino family within miles from where my family had settled; I remember we had to drive 25 minutes by car to buy our little plastic bags of rice from a small Chinese store. The few Filipinos we did meet were not from Cebu. Then when I left a couple of years later for Central Canada to a mid sized city in Southwest Ontario, called London, I could count with both my hands what we call “visible minorities” now. The odds were against my bumping into another Filipino much less a Cebuano. For the next twenty four years I was immersed in English and later French.

It was therefore not a surprise that when we landed in Cebu in 1998, I could not converse in our own Bisayan language. I could understand words, after thinking about it, but it was frustrating not to be able to respond. Or, by the time I knew what to say, the person who spoke to me was long gone.

When my family started touring the beach resorts, famous landmarks, old churches and my grandparents’ home where my grandfather delivered me, I realized how much of a foreigner I had become. I was no longer at home nor did I feel I belonged to my province of birth. The open fields near my childhood home where we played, had become “subdivisions”, using the term loosely, with rows and rows of houses as if they sprouted from the ground haphazardly. The coconut groves and sugar cane fields where we used to play cowboy and Indians, were now filled with little shacks and phone-booth sized stores selling everything from cooking oil to rubber slippers. I could not see my romantic memory of my native land for all the people, litter, potholes and loud corner clubs where no one danced but everyone got drunk.

My astute mother, who happened to be also vacationing in Cebu at that time, asked what was wrong with me. I responded hoping to hear an empathetic word from her, “I don’t think I am a Filipino anymore.” Instead, I got a lecture on how I should get off my high horse and recall that the things I was complaining about were in fact already there when I was growing up. Instead of being a victim of my surroundings, why don’t I think about what I could do in order to improve or change what I didn’t like.

She continued, ”You have heroes’ blood running in your veins. I expected more from you.” Now, you do not hear such a thing on a regular basis. I certainly didn’t feel like a hero, nor did I know anybody who was. I only read about them in books, and that was way back in grade school and high school. From that moment on I was all ears to what my Mom was saying. As we toured around the city, she said, “This is C. Padilla Street; this is named after your great great grandfather, Candido, who was my Mother’s grandfather. There is another street called T. Padilla, that stands for Toribio Padilla, a priest, and Candido’s uncle. Together they worked and fought with Leon Kilat to free Cebu of the Spanish occupation in 1898. That was exactly 100 years ago.”

I was shocked on so many levels. First of all, I did not know there was a Katipunero uprising in Cebu. I went to fairly good schools for my elementary and high school years, and all I could do was recite the names of Bonifacio, Mabini, del Pilar and of course Dr. Jose P. Rizal, down to his middle initial. Secondly, although I knew my Mom’s middle name was Padilla, I did not know that I was related to the “C. Padilla” directly and “T. Padilla” indirectly.

This revelation moved me. Suddenly I was looking at everyone I met, wondering if I was related to them. Suddenly, I felt for anyone who was not as lucky as I was, old men selling rusty tin cans and bottles for a measly two pesos. I felt for the street kids, who were running around and I wondered when they had their last meal and what did they eat? Did they go to school?

Before my family went back to Canada, my Mom gave me a few photocopied pages from a local newspaper. It was a centennial tome celebrating the 100th anniversary of the uprising on April 3, 1898. Without prompting, I realized now the origin of Tres de Abril Street. That’s where it all started.

The article was written by a Mr. Emil Justimbaste. I was hooked, and I learned more about the uprising in Cebu – this time however, the description of the planning and battles, and finally the capture of both C. Padilla and T. Padilla, and eventual execution of C. Padilla had a visceral effect on me. His blood flowed to the ground 100 years ago for fighting for something they believed in. They strongly believed that what they were doing would mean a better life for generations to come. My understanding of this event goes deeper than the simplistic “Filipinos against the Spaniards”. It was more of what they represented, what their roles were, that made their clash very poignant. In fact, most of the Katipuneros were Spanish-Filipino or Chinese-Filipino mestizos themselves. I was so glad to find out that there was a website where I could read more about the role of the Cebuanos during the 1898 revolution. I clicked on the site and there it was, in Mr. Justimbaste’s first chapter of “Leon Kilat and Cebu’s Revolution”:

“FRANCISCO Llamas. Nicolas Godines. Eugenio Gines. Luis Flores. Luis Abellar. Candido Padilla. Jacinto Pacana. Andres Abellana. Lucio Herrera. Mariano Hernandez. Nicomedes Machacon. Alejo Minoza. Ambrocio Pena. Hilario, Felix and Potenciano Alino. Estanislao Larrua. Pascasio Dabasol. Wenceslao Capala. Daniel Canedo. Silvestre and Simeon Canedo. Regino, Nicanor and Jaime Enriquez. Pantaleon Villegas (aka Leon Kilat). Bonifacio Aranas. Juan Climaco. Justo Cabajar. Florencio Gonzales. Arcadio Maxilom.

Sounds familiar? They should be. After all, many Cebuanos today bear the same family names, being their descendants. Streets are named after many of their ancestors. They - and several hundreds of others who participated in the Cebuanos' struggle against 400 years of Spanish colonial rule - are your local heroes.”

I agree these names are very familiar; I had classmates and friends with such names. I am sure, they too, were descendants of these heroes. I belong to this history. I belong to Cebu, no matter how long I have been away, nor how badly I speak the language. Reading this on the web completed the revelation that my Mom started during my 1998 vacation in Cebu. I urge all Bisaya, indeed all Filipinos to visit Mr. Justimbaste’s site: http://www.geocities.com/lkilat/. He truly is a hero of Cebu and I am very thankful for his research.

Now, it is 2008, ten years since my family vacation to Cebu, and I have been fortunate to visit again, this time for business. In fact, I have been back three times in the last six months. The city has progressed into a modern glass and steel urbanized area, much like other modern cities around the world. Coincidentally, through my old high school friends, Tito Tenazas and Ike Sepulveda, I was introduced to BisayaBulletin.com, which has made it possible for me to speak Bisaya with confidence again. Furthermore, the Trio Ladies, Teresa, Stella, and May, who started this site have been extremely welcoming, and probably unknowingly, are helping me through my journey back to being Bisaya. Thank you for allowing me to belong!

Celebrating our Mom's 75th Birthday at Seasons in Vancouver, March 2008. Standing L-R, Marc Canton, Christina Canton Arevalo, Peter Lee, Theresa Canton Lee, Blair McInnis, Mari-Anne Canton McInnis, Tracie Canton, Mannie Canton, Emily Canton McGovern, Ron McGovern. Seated, Dr. Candida Canceko (my Mom's sister), Mom, our Yaya Vering.